Effective Law Learning Strategies: Multisensory Law, Therapeutic Jurisprudence, and European Legal Education

Colette R. Brunschwig

2013-07-12 09:04I. The 33rd International Congress of Law and Mental Health: Panel on TJ and MSL

1. Conference Abstract as a Starting Point

2. Studying Law Effectively – or Not

3. Key Questions and Further Questions

4. Multisensory Law and Studying Law Effectively

5. Therapeutic Jurisprudence and Studying Law Effectively

6. Insights from Cognitive Psychology to Study Law Effectively

6.1 Encoding and Retrieval

6.2 Verbal and Sensory Learning Strategies

6.3 Visual Evidence: Verbal Learning Strategies

6.4 Visual Evidence: Verbo-Visual Organizing

6.5 Visual Evidence: Elaborating with the Senses

7. Insights from Neuropsychology to Study Law Effectively

7.1 Verbal Learning Strategies

7.2 Sensory Learning Strategies

7.3 Visual Evidence: Verbal Learning Strategies

7.4 Visual Evidence: Sensory Learning Strategies

8. Insights from Learning Psychology to Study Law Effectively

8.1 Procedural Structure of Learning Strategies

8.2 Visual Evidence and Procedural Structure of Learning Strategies

III. Results, Conclusions, and Outlook

3. Outlook: Hammurabi’s Code of Law

I. The 33rd International Congress of Law and Mental Health: Panel on TJ and MSL

This year, the International Academy of Law and Mental Health (see http://www.ialmh.org/template.cgi) is organizing the 33rd International Congress of Law and Mental Health in Amsterdam. This conference "brings together an international community of researchers, practitioners and professionals in the field whose wide range of perspectives contribute to a comprehensive picture of the main issues of law and mental health" (http://www.ialmh.org/template.cgi).

Why is this event relevant to the Community of Multisensory Law at C. H. Beck Publishers? It is important because there will be a panel on therapeutic jurisprudence (TJ) and multisensory law (MSL) on Monday, July 15, 2013, 4:00 P.M. – 6:00 P.M. I will come back to the terms MSL and TJ later.

Four presentations will be given:

- CAROLINE WALSER KESSEL (http://www.walserlaw.ch/), "A Visual Guide to the Swiss Protection of Adults and Children Law (2013): Applied Therapeutic Jurisprudence and Multisensory Law";

- ERNA HAUETER (http://www.haueteradvokatur.ch/), "Impulses from Multisensory Law and Therapeutic Jurisprudence for Better Coping with Client Stress during Separation and Divorce Proceedings";

- GEORG NEWESELY (https://www.fhg-tirol.ac.at/page.cfm?vpath=fachhochschule/forschung), "Promoting the Well-Being of Persons with Aphasia: Integrated Communicative Approaches from Therapeutic Jurisprudence and Multisensory Law";

- COLETTE R. BRUNSCHWIG (http://www.rwi.uzh.ch/oe/zrf/abtrv/brunschwig_en.html), "Introducing Multisensory Law and Therapeutic Jurisprudence into European Legal Education: Problems, Questions, and Tentative Answers."

As the presentation titles suggest, these are highly significant topics in terms of both legal research and practice. Since it might be interesting for readers to know more details, I shall outline the main points of my talk. Moreover, I shall add a few points which cannot be included in the presentation for time reasons. Should the other presenters wish me to outline their own presentations, I shall do so in further postings. At this juncture, I wouldn’t want to miss the opportunity of inviting you to join our TJ and MSL-panel in Amsterdam. After the conference, this posting might serve as a memo of the other presentations and of mine.

II. Introducing Multisensory Law and Therapeutic Jurisprudence into European Legal Education – Problems, Questions, and Tentative Answers

1. Conference Abstract as a Starting Point

In my conference abstract, I have raised many basic questions, such as "How are MSL and TJ already taught at law schools, especially in the English-speaking world?" "How could MSL and TJ be taught at European, in particular at Swiss law schools?" As regards the second question, I have raised further questions, such as "Could European and Swiss law schools in particular adopt the existing MSL and TJ curricula or at least some relevant courses from other law schools?" "Could MSL and TJ also be integrated into the teaching of other legal disciplines? If so, how?"

2. Studying Law Effectively – or Not

Given the content of my abstract, I would like to raise some background questions: First, do you know how to study the law most effectively? Second, which learning strategies did you and do you still use to study law? Third, should you be a law teacher, do you already teach your students effective learning strategies? And if you do, which ones?

I know from personal experience that I probably got it all wrong. How about you? TJ adopts insights from various branches of psychology. The same applies to MSL. I would argue that cognitive psychology, neuropsychology, and learning psychology provide us with particularly relevant insights into effective learning (and by implication, teaching). The difficulty perhaps is that so far we—I mean we as law students or lawyers—haven’t paid sufficient attention to these insights. I am convinced we should.

3. Key Questions and Further Questions

Paying attention to these insights leads to two key questions: From a TJ perspective, how might law students and lawyers learn effectively to promote their own well-being given the insights of cognitive psychology, neuropsychology, and learning psychology? From a MSL perspective, how might law students and lawyers use their various senses to promote effective learning? Both questions are linked to how "MSL could be integrated into the teaching of other legal disciplines at European law schools. And if so, how?"

The key questions just raised lead to further questions: Which effective learning strategies do the various branches of psychology suggest? Which of these strategies might be adopted by TJ and / or MSL? Since MSL and TJ are still rather unknown in the context of this community, they require a few introductory remarks, especially as regards studying law effectively.

4. Multisensory Law and Studying Law Effectively

Put simply, MSL focuses on the sensory phenomena of the law, be they, for instance, visual, olfactory (that is, unisensory), or audio-visual, and tactile-kinesthetic (that is, multisensory) (see Colette R. Brunschwig, "Law is Not or Must Not Be Just Verbal and Visual in the 21st Century: Toward Multisensory Law," in Nordic Yearbook of Law and Informatics 2010-2012, Internationalisation of Law in the Digital Information Society, eds. Dan Jerker B. Svantesson & Stanley Greenstein (Copenhagen: Ex Tuto Publishing, 2013), 240 sqq.). Following LIONEL BENTLY, how does or how might law use the senses? How does or how might law sense? (see Lionel Bently, "Introduction," in Law and the Senses: Sensational Jurisprudence, eds. Lionel Bently and Leo Flynn (London, Chicago, IL: Pluto Press, 1996), 2). And following ANDREAS PHILIPPOPOULOS-MIHALOPOULOS & JULIA CHRYSSOSTALIS, how does law relate to the senses? (see Andreas Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos and Julia Chryssostalis, "Introduction: Law and Taste," Law and the Senses Series (2013): 3 (available online at: http://nonliquetlaw.wordpress.com/).

What do these questions tell us about the relationship between MSL and studying law effectively? Considering this relationship means focusing on the sensory phenomena involved in studying law and asking how law students and lawyers might use their various senses. So, following BENTLY, how might law students and lawyers sense while studying law? And following PHILIPPOPOULOS-MIHALOPOULOS & CHRYSSOSTALIS, how might law students and lawyers relate to the senses while studying law? My tentative answer to these questions is that we need to adopt the insights of relevant branches of psychology, such as cognitive psychology, neuropsychology, and learning psychology.

5. Therapeutic Jurisprudence and Studying Law Effectively

The late BRUCE J. WINICK, one of the co-founders of TJ, observed: "Therapeutic jurisprudence is an interdisciplinary approach to legal scholarship and law reform that sees law itself as a therapeutic agent. The basic insight of therapeutic jurisprudence is that legal rules, legal practices, and the way legal actors (such as judges, lawyers, governmental officials, police officers, and expert witnesses testifying in court) play their roles impose consequences on the mental health and emotional wellbeing of those affected. Therapeutic jurisprudence calls for the study of these consequences with the tools of behavioural sciences. The aim is to better understand law and how it applies to minimize its anti-therapeutic effects and maximize its therapeutic potential. Therapeutic jurisprudence is interdisciplinary in that it brings insights from psychology and the social sciences to bear on legal questions, and it is empirical in that it calls for the testing of hypotheses concerning how the law functions and can be improved" (Bruce J. Winick, "Therapeutic Jurisprudence: Enhancing the Relationship Between Law and Psychology," in Law and Psychology: Current Legal Issues, Vol. 9, eds. Belinda Brooks-Gordon and Michael Freeman (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 32.

What can we draw from WINICK’s observations in view of the relationship between TJ and studying law effectively? Thinking about this relationship involves exploring how legal actors, such as law students and lawyers might learn effectively so that their mental, emotional, and physical well-being is or rather might be promoted. The purpose of this epistemic endeavor is to better understand studying law and how it might be accomplished so as to minimize potential antitherapeutic learning effects and maximize the therapeutic potential of learning.

These remarks might sound strange to the ears of European lawyers, particularly to lawyers in German-speaking jurisdictions. They might even frown at them. However, I would like to encourage German-speaking lawyers to learn from MARGRET ARNOLD that good feelings, such as "high challenge," have a positive impact on learning (Margret Arnold, Aspekte einer modernen Neurodidaktik: Emotionen und Kognitionen im Lernprozess [Aspects of Modern Neurodidactics: Emotions and Cognitions in the Learning Process] (Munich: Verlag Ernst Vögel, 2002), 123 sqq.) As a consequence, these feelings promote well-being, that is, they have a therapeutic effect. Negative feelings, however, such as fear or feeling threatened, impede or reduce learning (see Arnold, loc. cit., 124 sqq.). Hence, they promote "bad-being" (I mean the contrary of well-being), that is, they have an antitherapeutic effect.

6. Insights from Cognitive Psychology to Study Law Effectively

Cognitive psychology distinguishes two processes for coping sustainably with information, or in our context learning material: First, encoding, that is, "the process used to get information into LTM [long-term memory]" (E. Bruce Goldstein, Cognitive Psychology (Australia: Wadsworth Cengage Learning, 2011), 173); and second, retrieving encoded material from memory (see Goldstein, loc. cit., 181 sq.). Various principles for encoding and retrieval can be used for studying effectively (see Goldstein, loc. cit., 187). In what follows, I present these learning strategies.

6.2 Verbal and Sensory Learning Strategies

There are various verbal and sensory learning strategies for promoting effective studying.

Verbal strategies include reconstructing learning material, first by voicing such material and/or second by explaining it to others. Both strategies strengthen encoding (see Alexander Renkl and Matthias Nückles, "Strategien der externen Visualisierung [External Visualization Strategies]," in Handbuch Lernstrategien [Handbook Learning Strategies], eds. Heinz Mandl and Helmut Felix Friedrich (Göttingen et al.: Hogrefe, 2006), 135 sqq.; Goldstein, loc. cit., 188). Another means of effective verbal encoding is self-testing, that is, to "read a text with the idea of making up questions" or to read it "with the idea of answering questions later" (Goldstein, loc. cit., 188; original italics).

Organizing learning material verbo-visually increases long-term memory, too (see Goldstein, loc. cit., 188; see also Alan Baddeley, "Episodic Memory: Organizing and Remembering," in Memory, eds. Alan Baddeley, Michael W. Eysenck, and Michael C. Anderson (Hove, New York, NY: Psychology Press, 2009), 104). Elaborating this material with the senses constitutes another sensory learning strategy (see Goldstein, loc. cit., 173 sqq.). Using imagery strategies, we can imagine real or fictitious objects and/or situations in which our learning material might be relevant (see Maria Bannert and Wolfgang Schnotz, "Vorstellungsbilder und Imagery-Strategien [Imagination Images and Imagery Strategies]," in Handbuch Lernstrategien [Handbook Learning Strategies], eds. Heinz Mandl and Helmut Felix Friedrich (Göttingen et al.: Hogrefe, 2006), 74; Goldstein, loc. cit., 173 sqq.). As a rule, the imagery addresses the visual modality. But it can also refer to auditory, tactile, and other sensory modalities (see Bannert & Schnotz, loc. cit., 75). Furthermore, we can ask how any given learning material relates to what we already know (see Goldstein, loc. cit., 173 sqq.; similarly, see Baddeley, loc. cit., 103). To activate our existing knowledge, we can, for instance, use brainstorming or mapping (Ulrike-Marie Krause and Robin Stark, "Vorwissen aktivieren [Activating Foreknowledge]," in Handbuch Lernstrategien [Handbook Learning Strategies], eds. Heinz Mandl and Helmut Felix Friedrich (Göttingen et al.: Hogrefe, 2006), 43 sq.). To conclude this section, I would like to draw your attention to SHAMS & SEITZ (see http://shamslab.psych.ucla.edu/~lshams/; http://www.faculty.ucr.edu/~aseitz/), who emphasize the benefits of multisensory learning (see Ladan Shams and Aaron R. Seitz, "Benefits of multisensory learning," Trends in Cognitive Science 12, No. 11 (2008): 411 sqq.).

6.3 Visual Evidence: Verbal Learning Strategies

Let me illustrate how these strategies from cognitive psychology can help students learn verbally about visual evidence in civil procedure.

My example is Art. 177 of the Swiss Code of Civil Procedure. "Physical records – definition The following are considered to be physical records: papers, drawings, plans, photos, films, audio recordings, electronic files and the like that are suitable to prove legally relevant facts. [Urkunde – Begriff Als Urkunden gelten Dokumente wie Schriftstücke, Zeichnungen, Pläne, Fotos, Filme, Tonaufzeichnungen, elektronische Dateien und dergleichen, die geeignet sind, rechtserhebliche Tatsachen zu beweisen.]" (see http://www.admin.ch/ch/e/rs/2/272.en.pdf).

In terms of reconstructing learning material, law students could paraphrase the content of the norm by speaking it aloud. They could explain, for instance, to their colleagues which examples of visual evidence this provision alleges.

In terms of self-testing, another strategy suggested by cognitive psychology, students could consider the following questions while reading Art. 177: "What is visual evidence?" "Does Swiss jurisdiction know this term?" "Which examples of visual evidence does Art. 177 allege?" "Would there be other examples of visual evidence. If so, which?" Or they could think of answering questions about this norm in a later examination.

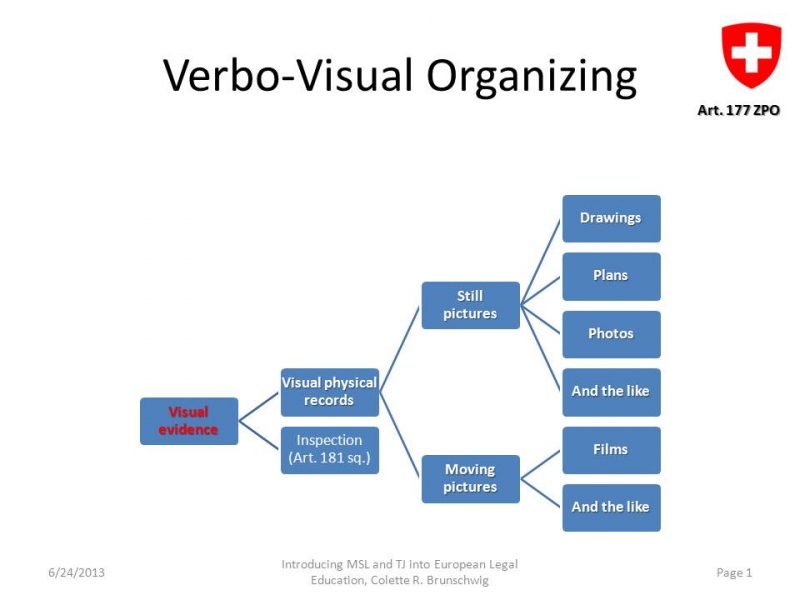

6.4 Visual Evidence: Verbo-Visual Organizing

Let’s turn to the first sensory learning strategy, that is, to verbo-visual organizing.

This chart shows how students might verbo-visually organize the learning topic "Visual Evidence in Civil Procedure." FRITJOF HAFT also advocates for verbo-visually structuring legal learning material (see Fritjof Haft, Juristische Lernschule: Anleitung zum strukturierten Jurastudium [Juridical Learning School: Guide to Structured Legal Studies] (München: edition normfall, 2010), 192 sqq.). If I understand the author correctly, he would probably call this type of legal visualization a concept tree: "Im (kontinentaleuropäischen und ganz besonders im deutschen) Recht, […], spielen Begriffsbäume eine Hauptrolle. […] Hierarchische Strukturen werden für Ihr Lernen eine Hauptrolle spielen. Ihr wesentliches Training wird darin bestehen, die Fertigkeit einzuüben, in einem beweglichen Verbund von Begriffshierarchien zu navigieren. [In (continental European and particularly in German) jurisdictions, […], concept trees play a leading role. […] Hierarchical structures will play a dominant role in your learning. Your fundamental training will consist of practicing how to navigate in a flexible network of concept hierarchies] (Haft, loc. cit., 199).

6.5 Visual Evidence: Elaborating with the Senses

Adopting legal imagery strategies will help law students imagine how visual evidence might be relevant to them.

Imagining themselves as tort lawyers or building lawyers, law students might realize that they might need to know how to persuade the court both auditorily and visually, that is, multisensorily.

Or imagining themselves as judges, students might realize how necessary it is to know how to deal with visual evidence professionally, that is, according to which criteria visual evidence can be admitted and considered.

Ascertaining what they already know about visual evidence, law students might also relate this learning topic to pictures of accident or crime victims that they have seen in the mass media or even on the Internet (see, e.g., http://www.seacoastvideo.com/legal-video-production/multimedia/).

7. Insights from Neuropsychology to Study Law Effectively

In what follows, I am going to present learning strategies suggested by neuropsychology. Since neuropsychology relates to neuroscience and psychology, I shall also draw on insights from neuroscience, particularly on contemplative neuroscience (see http://www.mindful.org/the-science/the-emergence-of-contemplative-neuroscience). The latter explores mindfulness or mindfulness meditation and its effects, for instance on mental, emotional, and physical health. There is already a legal discourse on mindfulness or mindfulness meditation. This discourse adopts insights from neuroscience. That is why I shall consider this legal discourse as well. Again, it is safe to distinguish between verbal and sensory learning strategies for promoting effective studying.

7.1 Verbal Learning Strategies

Students learn more effectively if their learning process involves social interaction (see Margret Arnold, "Brain-based Learning and Teaching – Prinzipien und Elemente, [Brain-Based Learning and Teaching – Principles and Elements]," in Neurodidaktik: Grundlagen und Vorschläge für gehirngerechtes Lehren und Lernen [Neuropedagogy: Fundamentals and Suggestions for Brain-Appropriate Teaching and Learning], ed. Ulrich Herrmann, 2nd ed., (Weinheim, Basel: Beltz Verlag, 2009), 190). Therefore, if students communicate with their fellow students and/or friends about their learning material on a personal and, I would add, regular basis, this contributes to effective studying.

Students learn effectively if their learning material and experiences evoke positive emotions (see Arnold, loc. cit., 190). More specifically, it is important that learning inspires and delights students (see Gerald Hüther, "Für eine neue Kultur der Anerkennung: Plädoyer für einen Paradigmenwechsel in der Schule, [For a new Culture of Recognition: Plea for a Paradigm Shift at School]," in Neurodidaktik: Grundlagen und Vorschläge für gehirngerechtes Lehren und Lernen [Neuropedagogy: Fundamentals and Suggestions for Brain-Appropriate Teaching and Learning], ed. Ulrich Herrmann, 2nd ed., (Weinheim, Basel: Beltz Verlag, 2009), 205). These positive learning effects can be achieved through both verbal and sensory learning strategies.

7.2 Sensory Learning Strategies

ARNOLD states that learning is more effective if learners are provided with experiences that address their various senses (see Arnold, loc. cit., 190).

PETER GASSER, another neuropsychologist, suggests kinesthetic learning strategies, that is, to move during the learning process and/or to move between learning sequences (see Peter Gasser, Gehirngerecht lernen: Eine Lernanleitung auf neuropsychologischer Grundlage [Brain-Suitable Learning: A Guidance for Learning Based on Neuropsychology](Bern: hep verlag, 2010), 69). Contemplative practices also have a positive impact on learning (see Peter Theurl "'Lernen unter Selbstkontrolle' – Entspannung und Kontemplation in Schule und Unterricht ['Learning with Self-Control' – Relaxation and Contemplation at School and in Teaching]", in Neurodidaktik: Grundlagen und Vorschläge für gehirngerechtes Lehren und Lernen [Neuropedagogy: Fundamentals and Suggestions for Brain-Appropriate Teaching and Learning], ed. Ulrich Herrmann, 2nd ed., (Weinheim, Basel: Beltz Verlag, 2009), 262). With this in mind, PETER THEURL suggests practicing progressive muscle relaxation between learning sequences (see Theurl, loc. cit., 265 sq.).

A further contemplative practice for improving learning is mindfulness (see http://www.contemplativemind.org/). There are many definitions of mindfulness. According to LEONARD L. RISKIN (see http://www.law.ufl.edu/faculty/leonard-l-riskin), mindfulness "means being aware, moment-to-moment, without judgment and without commentary, of whatever passes through the sense organs and the mind—sounds, sights, bodily sensations, odors, thoughts, judgments, images, emotions. One develops the ability to be mindful through 'formal' practices, such as meditation and mindful yoga, then deploys mindfulness in everyday life." (Leonard L. Riskin, "Awareness in Lawyering: A Primer on Paying Attention," in The Affective Assistance of Counsel: Practicing Law as a Healing Profession, ed. Marjorie A. Silver (Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press, 2007), 447). As has become clear, there are many ways of practicing mindfulness. Here, I would like to focus on the sensory or rather multisensory (meditation) practices, such as breathing, sensing (scanning the body), shifting attention to different sensory modalities, and visualizing (see, e.g., Philippe Goldin, Cognitive Neuroscience of Mindful Meditation, February 28, 2008, available online at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sf6Q0G1iHBI).

Referring to JON KABAT-ZINN (http://www.umassmed.edu/Content.aspx?id=43102), RISKIN describes the purpose of mindfulness, "to live with more freedom from habitual ways of perceiving and acting, and thus to be more present in your life and work, to enjoy life more, and to help others more readily and fully" (Riskin, loc. cit., 449). To practice mindfulness or mindful meditation can have many positive effects. For instance, it improves concentration and attention (see http://www.mindfulnet.org/page7.htm), and reduces stress (see Christian Stock, Achtsamkeitsmeditation: Übungen für mehr Gelassenheit im Leben [Mindfulness Meditation: Exercises for More Serenity in Life] (Stuttgart: Trias Verlag, 2012), 10). It goes without saying that all these effects are crucial for effective studying.

SCOTT L. ROGERS encourages law students to do an exercise that involves their hands and breathing: "1. Sit in a chair—hands resting on your lap, each in a gentle grip. 2. Bring awareness to your hands and to your breathing. 3. Inhale and extend your fingers fully to the count of four. 4. Hold your breath and keep your fingers extended to the count of seven. 5. Exhale and close your hands to the count of eight. 6. Repeat this exercise two to four times" (Scott L. Rogers, Mindfulness for Law Students: Using the Power of Mindful Awareness to Achieve Balance and Success in Law School (Miami Beach: Mindful Living Press, 2009), 43; see also http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MTbhxHWnE3U). Elsewhere, ROGERS inspires law students to do an olfactory exercise. The smell of peppermint "is associated with an increase in memory and alertness" (Scott, loc.cit., 67). Mindfulness is already taught at law schools (see Leonard L. Riskin, "The Contemplative Lawyer: On the Potential Contributions of Mindfulness Meditation to Law Students, Lawyers, and their Clients," Harvard Negotiation Law Review, Multidisciplinary Journal on Dispute Resolution (2002): 33 sqq.; Rhonda V. Magee, "Educating Lawyers to Meditate?" UMKC Law Review 79, no. 3 (2011): 535 sqq.; http://www.law.berkeley.edu/mindfulness.htm).

Although PHILIPPOPOULOS-MIHALOPOULOS does not draw on neuropsychology, he encourages law students to walk the city, asking themselves where the law is in the city and whether it determines where they can walk or not. The author invites to use their various senses while they are moving through town (see Andreas Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos, "Mapping the Lawscape: Spatial Law and the Body," in The Arts and the Legal Academy: Beyond Text in Legal Education, eds. Zenon Bańkowski, Maksymilian Del Mar, and Paul Maharg (Farnham, Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2013), 125 sqq.). In this multisensory way, law students might learn property law, building law, spatial planning law, and so forth.

7.3 Visual Evidence: Verbal Learning Strategies

THORSTEN DEPPNER et al. encourage law students to learn together in study groups (Thorsten Deppner et al., Examen ohne Repetitor: Leitfaden für eine selbstbestimmte und erfolgreiche Examensvorbereitung [Exam without Tutor: Introduction to Self-Paced and Successful Exam Preparation], 3rd ed. (Baden-Baden: Nomos, 2011), 44). The authors note that learning in such a group has many benefits: "Sie motiviert und ermöglicht eine Lernkontrolle. Das Lernen gestaltet sich interaktiv: Es wird diskutiert, nachgefragt und erklärt, und das führt dazu, dass alle Beteiligten den Stoff besser verstehen. [It motivates and makes learning control possible. Learning becomes interactive: There is discussion, inquiry and explanation, and this leads to better understanding of the subject matter on the part of the participants]" (Deppner et al., loc. cit., 44; similarly, see Haft, loc. cit., 253). DEPPNER et al. recommend law students to solve two types of cases with one another: "small" cases for oral exams, "large" cases for written exams (Deppner et al., loc. cit., 65 sqq.). As it is not possible to learn law by "merely" solving cases, DEPPNER et al. suggest querying, giving small lectures on learning issues, and discussing (the latter would involve role playing) in study groups (see Deppner et al., loc. cit., 67 sq.). All these various learning strategies could be pursued with regard to visual evidence in civil procedure.

If the members of a law study group interact with each other both in a business-like and friendly way about, for instance, visual evidence in civil procedure, this should elicit positive emotions. A study group can be an opportunity to become friends and to share good experiences, such as cooking and eating together after or between learning phases (see Deppner et al., loc. cit., 131).

7.4 Visual Evidence: Sensory Learning Strategies

To stimulate themselves audio-visually, law students could turn to the Visual Persuasion Project-Website (see http://www.nyls.edu/centers/projects/visual_persuasion), watch films, and ask themselves whether, and if so, how the insights provided by this Website might be adopted mutatis mutandis to visual evidence in the civil procedure of their own jurisdictions. Expanding on visual legal training, RICHARD K. SHERWIN explains persuasively how law students (might) learn visual evidence (see http://www.nyls.edu/centers/projects/visual_persuasion/visual_legal_training).

DEPPNER et al. recommend law students who study alone to relax and to take their minds off the learning material: "Sehr wirksam sind die verschiedenen Entspannungstechniken wie Autogenes Training, Yoga oder progressive Muskelentspannung. Mit ihnen kann eine sogenannte Tiefenentspannung erreicht werden, die erholsamer sein kann als ein unruhiger Schlaf. Der einzige Nachteil der Entspannungstechniken ist der, dass sie gelernt werden müssen. [Various relaxation techniques, such as autogenic training, yoga, or progressive muscle relaxation, are very effective. Applying them helps one achieve deep relaxation that is more restorative than restless sleep. Their only disadvantage is that they have to be learned.]" (Deppner et al., loc. cit., 108). However, mindfulness for law students and lawyers does not require a considerable learning effort. At least some of its multisensory exercises are quite simple to grasp. This does not mean that they are easy to practice. They require patience and perseverance. Mindfulness can be practiced whether law students learn alone and / or with others. I do not quite understand why DEPPNER et al. make their relaxation recommendations only for law students who learn alone.

To study visual evidence with more concentration and attention and with less stress, law students and lawyers could practice relaxation techniques and / or mindfulness (meditation).

8. Insights from Learning Psychology to Study Law Effectively

8.1 Procedural Structure of Learning Strategies

To some extent, learning psychology recommends the same or similar learning strategies as cognitive psychology and neuropsychology (see, e.g., Karl Josef Klauer and Detlev Leutner, Lehren und Lernen: Einführung in die Instruktionspsychologie [Teaching and Learning: Introduction into Educational Psychology], 2nd ed. (Weinheim, Basel: Beltz, 2012), 164). Instead of reiterating these strategies, I would like to introduce a model developed by learning psychology. It concerns the procedural structure of learning strategies (see Klauer & Leutner, loc. cit., 163, table 15.2, and 174).

It would be interesting to compare this model with a model developed by GASSER (see Gasser, loc. cit., 92, fig. 92). GASSER’s model draws on neuropsychology. In the section "elaboration strategies," he mentions multisensory learning.

8.2 Visual Evidence and Procedural Structure of Learning Strategies

In the preparation phase, law students could determine their learning objectives with respect to visual evidence. More specifically, their learning objective would consist of being able to deal with such evidence professionally as a lawyer and judge. They could figure out how much time they would need for studying visual evidence and in which social and spatial context they would like to study it. Law students could motivate themselves, for instance, by telling themselves that they are equipped with the required skills to become visually literate about visual evidence. They could get themselves interested in mastering this learning topic and in passing an examination on civil procedure. In the execution phase, law students could try out various information acquisition, processing, encoding, and retrieval strategies in view of learning visual evidence. In the conclusion phase, law students could role-play to be visual legal advocates or judges who have to admit and consider visual evidence. Again, I am referring to Swiss jurisdiction.

The model presented above might help law students and / or lawyers to orient themselves where they stand in their learning process, for example, with respect to visual evidence. Depending on the different aspects of visual evidence, I imagine that learners might wander back and forth between the three learning strategy phases.

III. Results, Conclusions, and Outlook

Obviously, a lot more could be written about how MSL and TJ might be introduced into European legal education. The above points are no more than preliminary and tentative steps. All these learning strategies go to the heart of TJ, which aims to promote law students’ and lawyers’ well-being. They also go to the heart of MSL, which aims to foster law students’ and lawyers’ effective learning through involving their various senses. MSL and TJ might be legal disciplines to adopt these insights and to offer them to other legal disciplines, primarily to legal education.

As we have seen, there is already some German-speaking literature on how to study law effectively. In their appendix, DEPPNER et al. provide a useful list of references (see Deppner et al., 213 sq.). This posting has attempted to give a small account of this literature’s insights. DEPPNER et al., for instance, draw on learning theory and learning psychology (see Deppner et al., loc. cit.,215), whereas HAFT primarily relies on his extensive and long experience as a law professor. It strikes me that the English-speaking legal discourse on contemplative practices, such as mindfulness or mindfulness meditation, has not been adopted yet, at least not in these two books. I do not know about the other German-speaking publications on legal learning strategies.

In any case, if we adopt the learning strategies described by the various branches of psychology, each law studying and learning day holds great promise and endless possibilities.

I would warmly recommend not only TJ and MSL, but also other legal disciplines to teach these and related learning strategies.

I would recommend students and practicing lawyers to read HAFT’s Juristische Lernschule: Anleitung zum strukturierten Jurastudium [Juridical Learning School: Guide to Structured Legal Studies]. This book is a rich and precious source and transforms studying law into an inspiring experience. I would also recommend DEPPNER’s et al. Examen ohne Repetitor: Leitfaden für eine selbstbestimmte und erfolgreiche Examensvorbereitung [Examination Preparation without a Tutor: Introduction to Self-Paced and Successful Exam Preparation]. As has been shown, this book gives useful tips on how to study law effectively. At this juncture, I would encourage DEPPNER et al. to lay open their psychological sources also in the main text and not only in the list of references. "Ethics, copyright laws, and courtesy to readers require authors to identify the sources of direct quotations or paraphrases and of any facts or opinions not generally known or easily checked ([…])" (University of Chicago, ed., The Chicago Manual of Style: The Essential Guide for Writers, Editors, and Publishers, 16th ed. (Chicago, IL, London: University of Chicago Press, 2010), 655 n 14.1). In any case, I would have been most grateful if these two books had already been available during my law studies.

How does the learning content influence our choice of learning strategies? Since “[e]ach brain is uniquely organized” (Arnold, loc. cit., 189), which learning preferences do we have as individuals? I would encourage readers to consider these questions. The further we advance in our legal profession, the more we have to learn on our own. We have to study law during our entire professional career. Since our whole legal learning life is at stake, it is necessary to find our own learning style consciously. Let us remain open to the surprises of various learning strategies offered by cognitive psychology, neuropsychology, and learning psychology, be they verbal and / or multisensory.

3. Outlook: Hammurabi’s Code of Law

As a result, TJ and MSL might also appeal to European law schools, especially since these legal areas are still not taught in Europe in general or in Switzerland in particular and if they are, then only marginally.

I would like to close with a picture. It shows the upper part of the front view of a basalt stele. This stele incorporates Hammurabi’s Code of Law. Hammurabi was a king of the Babylonian Empire (see Claire Iselin, "Law Code of Hammurabi, king of Babylon," [s.p.], available online at: http://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/law-code-hammurabi-king-babylon).

Source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Codice_di_hammurabi_03.JPG

In the above pictorial relief, Hammurabi receives his royal insignia from Shamash, a sun god and god of justice in the Babylonian pantheons. In the textual relief, we can see Hammurabi’s Code of law, written in cuneiform. The Code deals with different legal matters (see Iselin, loc. cit., [s.p.]).

Why am I presenting Hammurabi’s stele here? There are many translations of his name (see J. Dyneley Prince, "The Name Hammurabi," Journal of Biblical Literature 29, no. 1 (1910): 21; D. D. Luckenbill, "The Name Hammurabi," Journal of the American Oriental Society 37 (1917): 250 – 252). According to DYNELEY, for instance, Hammurabi means "'Ammu is the healer'" (see Dyneley, loc. cit., 23). And "[…] Ammu is the name of a god" (Prince, loc. cit., 22).

I am not sure whether the "Healer’s Code of Law" had a therapeutic effect or not (on Hammurabi’s Code, see, e.g., Hugo Winckler, Die Gesetze Hammurabis in Umschrift und Übersetzung [The Laws of Hammurabi Transcribed and Translated], 2nd ed. (1904; repr., Paderborn: Salzwasser Verlag, 2013). Nevertheless, I suppose that HAMMURABI’s laws could be seen, touched, and perhaps also smelled. It was and is still even possible to move in front of or around the stele while learning the Code. Among other functions, it served as an educational tool (see Iselin, loc. cit., [s.p.]). Thus, this sculpture allowed and still allows for studying law multisensorily.

Drawing both on cognitive science and neuroscience, SOPHIA LYCOURIS & WENDY TIMMONS point out "the physical roots of mental processes" and stress "the importance of bodily experiences within legal education through references to dance education" (Sophia Lycouris and Wendy Timmons, "Physical Literacy in Legal Education: Understanding Physical Bodily Experiences in the Dance Environment to Inform Thinking Processes within Legal Education," in The Arts and the Legal Academy: Beyond Text in Legal Education, eds. Zenon Bańkowski, Maksymilian Del Mar, and Paul Maharg (Farnham, Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2013), 51). LYCOURIS & TIMMONS posit "that bodily practices such as dance can contribute to the development of ethical and moral reasoning" (Lycouris & Timmons, loc. cit., 52). The authors describe movement improvisation "as the 'spontaneous creation of form and content' ([…])" (Lycouris & Timmons, loc. cit., 56). Referring to ANNA HALPRIN (see http://www.annahalprin.org/) and SIMONE FORTI (http://www.wacd.ucla.edu/simone-forti), the authors refer to improvisation "as a way of finding solutions to problems" (Lycouris & Timmons, loc. cit., 56). "Forti was interested in how problems always exist within given [legal; my insertion] contexts and the importance of good observation skills in working with them. […] Forti developed a technique of using various combinations of [legal; my insertion] text with movement, both as preparation for performance and performance mode"( Lycouris & Timmons, loc. cit., 58 sq.). I inserted "legal" to raise the awareness that these texts might have legal contents, too.

Hammurabi’s Code describes "almost three hundred laws and legal decisions governing daily life in the kingdom of Babylon" (Iselin, loc. cit., [s.p.]). May readers forgive me for imagining law students improvising the situations and stories that underlie these laws and legal decisions. Thus, such improvisation could also contribute to the development of their legal reasoning. It would not be a dance around the golden calf, but a dance around the "Healer’s Code of Law" at the Louvre (see http://www.louvre.fr/en). Or, and I shall close on this note, an artistic strategy for learning about legal history.

Given "Hammurabi’s Code of Law," I would argue that the answers to the present and future questions about studying law might also lie in the past.

Hinweise zur bestehenden Moderationspraxis

Kommentar schreiben